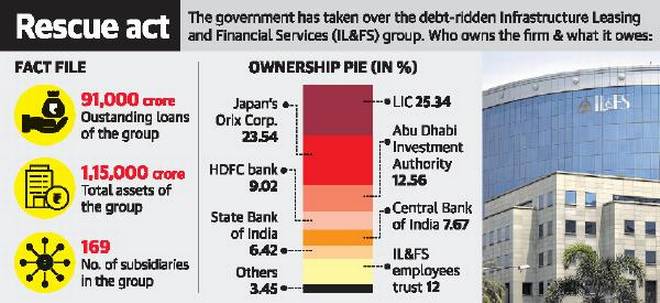

As the world marked the 10th anniversary of the collapse of Lehman Brothers which triggered the global financial crisis in September 2008, India’s leading infrastructure finance company IL&FS defaulted on payments to lenders triggering panic in the markets. It has 91,000 crore debt. The company’s default spells trouble for its investors, which include banks, insurance companies, and mutual funds. Investors and traders have been worried over the cascading effects of IL&FS’s defaults. The government finally intervened in the IL&FS crisis superseding its board and appointing new members, with banker Uday Kotak as chairman. What is IL&FS? What is IL&FS crisis? Why is IL&FS “too big to fail” and what is “shadow bank”

Table of Contents

What is IL&FS?

IL&FS Ltd, or Infrastructure Leasing & Finance Services, is a core investment company and serves as the holding company of the IL&FS Group. The company has built the country’s first toll road and also the longest tunnel. The company has 160 subsidiaries and four associate companies. The erstwhile giant has invested heavily in roads, ports and construction. A brain child of the late MJ Pherwani, IL&FS was founded in 1987 with equity from Central Bank of India, Unit Trust of India and Housing Development Finance Co to fund infrastructure projects when peers IDBI and ICICI were focused more on corporate projects.

IL&FS has institutional shareholders including SBI, LIC, ORIX Corporation of Japan and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA). As on March 31, 2018, LIC and ORIX Corporation are the largest shareholders in IL&FS with their stakeholding at 25.34 per cent and 23.54 per cent, respectively. Other prominent shareholders include ADIA (12.56 per cent), HDFC (9.02 per cent), CBI (7.67 per cent) and SBI (6.42 per cent).

The subsidiaries of IL&FS include transportation network building subsidiary IL&FS Transportation Networks Ltd (ITNL), engineering and procurement company IL&FS Engineering and Construction Co. Ltd and financier IL&FS Financial Services Ltd.

What is IL&FS crisis?

As infrastructure became the central theme in the past two decades, IL&FS used its first mover advantage to lap up projects. But the 2013 land acquisition law made many of its projects unviable. Cost escalation also led to many incomplete projects. Lack of timely action exacerbated the problems.

A plan to raise funds by selling stake to Piramal Enterprises Ltd., controlled by billionaire Ajay Piramal, in 2015 was rejected by the shareholders. That prompted the firm, which lent for projects that take years to complete, to seek short-term funds, according to the director.

The slowdown in infrastructure projects and disputes over contracts locking about Rs 90 billion of payments due from the government have further worsened the condition.

The company piled up too much debt to be paid back in the short-term while revenues from its assets are skewed towards the longer term. IL&FS is sitting on a debt of about Rs 91,000 crore. Of this, nearly Rs 60,000 crore of debt is at a project level, including road, power and water projects. In the process, it has built up a debt-to-equity ratio of 18.7.

IL&FS first shocked markets when it postponed a $350 million bonds issuance in March 2018 due to demand for a higher yield from investors.

IL&FS Financial Services, a group company, defaulted in payment obligations of bank loans (including interest), term and short-term deposits and failed to meet the commercial paper redemption obligations due on September 14.

On September 15, the company reported that it had received notices for delays and defaults in servicing some of the inter corporate deposits accepted by it.

Consequent to defaults, rating agency ICRA downgraded the ratings of its short-term and long-term borrowing programmes. The defaults also jeopardised hundreds of investors, banks and mutual funds associated with IL&FS. Investors and traders have been worried over the cascading effects of IL&FS’s defaults.

IL&FS defaulted DSP Credit Risk Mutual Fund commercial papers. These were rated as AAA. Due to the default of payment, DSP Mutual Fund was under pressure for redemptions from corporate clients. It cannot sell Govt bonds as the yield was high. When DSP Mutual Fund sold non-convertible debentures of the Dewan Housing Finance Corporation at a discount, the DHFL stock took a hammering. Debt market yields became up, which means bond prices are down and lenders want a higher return to bear the risk of lending cash.

The defaults by IL&FS shut it out of the market, leaving it at the mercy of shareholders — Life Insurance Corp of India, Housing Development Finance Corp, Japan’s Orix Corp and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority —they signed off on the Rs 4,500-crore rights share sale. The company identified at least 25 projects for sale, which include some road and power projects. With the asset sale plan, it would be able to bring down debt by about Rs 30,000 crore. But the problem is that the completion would take about 18 months.

How is Government Handling IL&FS crisis?

The government finally intervened in the IL&FS crisis on 1 Oct 2018, superseding its board and appointing new members, with banker Uday Kotak as chairman.

After a report from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs concluded that the affairs of the IL&FS holding company and its group companies were being conducted in a manner that was prejudicial to public interest, the government moved the National Company Law Tribunal(NCLT) for superseding the Board, which was granted with immediate effect.

The NCLT also approved the induction of six directors recommended by the government. “The new Board shall take up its responsibility with immediate effect, after following due procedures,” the Finance Ministry said in a statement.

A probe by the Serious Fraud Investigation Office has also been ordered into IL&FS and its subsidiaries following complaints.

“The government stands fully committed to ensure that needed liquidity is arranged for the ILFS from the financial system so that no more defaults take place and the infrastructure projects are implemented smoothly,” the Finance Ministry said.

Too Big to Fail

Too big to fail became common parlance during the 2008 subprime crisis, with America’s treasury department and regulatory authorities, including the Federal Reserve and the Securities and Exchange Commission, employing it to justify bailing out sundry private investment entities. The underlying concept is simple: an entity has vast exposure across the financial ecosystem and, for whatever reason, it’s unable to meet its obligations; if it defaults, its creditors will also be unable to meet their obligations, leading to contagious defaults. So, rescue the sick entity.

Such a rescue is morally ambiguous. It usually involves forgiving the entity’s transgressions and places a financial burden on the rescuers, which generally means taxpayers and shareholders of other institutions being dragged into the mess. It may be the pragmatic thing to do, however, if indeed the entity is too big to fail.

The cost of not saving IL&FS from sinking is going to be huge as the company reportedly accounts for nearly 0.7 percent of all banking loans, 2 percent of all outstanding commercial papers and 1 percent of debentures. Imagine the impact of nearly 1 percent of all banking loans turning non-performing asset in one go!

Shadow Bank or NBFC

“Shadow bank”, or shadow banking, is often used to describe informal or semiformal lenders in mainland China. Loosely, a shadow bank is an entity that offers financial services similar to a bank but without being part of the regulated banking system.

Shadow banks labour under one great disadvantage: they have a higher cost of funding. But the lack of regulatory oversight allows them to take on more risks than banks. So, they can cut corners and earn higher returns. They can also go bust more spectacularly

In India until about a month ago, shadow banks were known as non-banking financial companies, or NBFCs. There are thousands of them and they come in all shapes and sizes. Some have specialised briefs and, often, a majority government shareholding. The Power Finance Corporation, for example, has the government as the majority shareholder and does what its name suggests. Ditto for the Rural Electrification Corporation. There’s HDFC, the premier and pioneering housing mortgage lender, and there are specialists in vehicle finance, hypothecating both commercial and personal vehicles. There are retail lenders offering easy monthly instalment schemes for people buying fridges, mobile phones, laptops, lawn mowers, doing house improvements. There are NBFCs lending against gold and NBFCs offering personal loans for varied purposes.

One key area of NBFC operations is infrastructure financing. There are inherent technical and historical reasons banks are wary of infrastructure Infrastructure projects are long-gestation and high-risk. It takes years to lay a major road, build a port terminal, roll out a telecom network, begin a mining operation, or set up a power plant. They are capital-intensive, requiring vast sums of money, and the returns are zero until the project is up and running. There are political hurdles since land acquisition and regulatory clearances are always involved. The assets of an unfinished project – a half-built bridge, or a stalled power plant – are often worthless, so the lender can recover nothing by seizing assets. There are legal complications involved in seizing assets anyway. That is quite apart from the usual endemic contractual disputes.

NBFCs face asset-liability mismatches similar to banks but there are no Reserve Bank regulations preventing them taking such risks or limiting exposures. They borrow money and roll over loans while lending to high-risk infrastructure projects. They can make long-term returns that are well above the norm for banks.

Questions to ask in IL&FS Crisis? Can we trust the experts?

How did IL&FS run up a debt of Rs 91,000 crore (let’s spell it out: Rs 91,000,00,00,000)? Did it happen overnight? If it didn’t, as it obviously couldn’t, how did no one notice it till now? If it was noticed before, why didn’t its shareholders (LIC, SBI, Oryx Corp of Japan, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority being the major ones) call a halt and sack its management much, much earlier?

Is the idea of having independent directors mere eyewash? If the shareholder directors were sleeping, were the independent directors Rip van Winkles too? IL&FS had luminaries like R C Bhargava (chairman of Maruti Suzuki), Sunil Mathur (former chairman of LIC) and Jaithirth Rao (former country head of Citicorp) on the board for periods ranging from six to 28 years. Were they presented with lies, damned lies, and statistics? Or were they supplied with wool to pull over their eyes, or did they bring their own? Bhargava was also on the risk management committee, so essential in assessing infrastructure projects. Why did this committee not meet for three whole years (not two as reported)?

How is it that two rating agencies, allegedly run by professionals, continued to give IL&FS an AAA rating, and in less than two months have downgraded it to D (Default)?

The government stepped in on October 1. But just two days earlier, the company’s shareholders approved a Rs 4,500-crore rights issue. And a mere month before that, the company gave out a final dividend of 10%. (In the previous year, the dividend was 42.5%). IL&FS gave a 66% increase to its management staff, and chairman Ravi Parthasarathy gave himself a 144% increase, taking his salary to Rs 26.3 crore.

Three people ran IL&FS more or less from the start: Chairman Parthasarathy, VC and MD Hari Sankaran and Jt MD and CEO Arun Saha. Why were they allowed to run the company as a private fiefdom? Will there be an investigation into their assets now?

This is made worse because within the community there seems to be a reluctance to point fingers: for example, HDFC exited from the IL&FS board a year ago. If it did so in spite of having a 9% stake in the company, it must have been because it saw danger signs. Why did it not issue a quiet warning to everyone else?

Why would a company, which is not diversified, but involved in one basic activity, need so many subsidiaries, unless the idea was to have a large group of unlisted entities, which would, therefore, escape scrutiny? We thought only shady private companies do this to create a complex web of cross-holding and fudged accounts; but here’s a company whose large holding is with LIC and State Bank and therefore the government and, it follows, poor lay people like us.

What were the auditors doing all these years? They raised a red flag only this year, but the company is 31 years old. Does anyone remember Satyam Computers, the only other company to have been taken over by the government? It was found that its auditors were complicit in Satyam’s fraud. Will there be an audit of IL&FS auditors? Is there an inherent conflict of interest in the fact that auditors and rating agencies are paid by the companies they have to assess?

What the whole sorry IL&FS saga tells us is that we can’t trust the experts. There are exceptions of course, but many use their expertise to enrich themselves, or they don’t use their expertise and let others enrich themselves. A majority of us are not financial experts, and we inexpertly pay taxes and invest in companies and buy insurance policies, and then find the money going into deep, deep holes. So here are a layman’s naïve questions:

Related Articles:

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that you ought to write more on this subject matter, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people do not speak about such subjects.

To the next! All the best!!